On Nancy

Sinatra

by

Martin Scott

Reprinted by Permission of The Cimarron Review, Issue 138, Winter, 2002

|

On Nancy

|

|

|

W |

hen I was a child, somewhere in the throes of what was in the ‘70’s called junior high, my family did not go to church on Sunday morning. Instead, my stepfather would get up around nine and, in his white terrycloth robe, play records on his massive stereo system. This was in the days when components came wrapped in heavy furniture: impossible blocks of wood encasing a record player and amplifier in something like a short armoire or linen closet. There, behind sliding fabric doors, one kept one’s LP’s in a convenient slot between the speakers and the turntable. And every Sunday morning, Dick would play the same three of the twenty or so records he owned: The Supremes’ Greatest Hits, and a couple by Frank Sinatra. The only religion I knew had something to do with “Baby Love” and “Back in My Arms Again.” And the Chairman of the Board was more concerned with “Strangers in the Night” and the bluesy persistence of “That’s Life” than with the usual pieties one associates with worship. My brother and I woke to this music with a kind of joy, a kind of total pleasure in walking down the stairs. Sunday was a sonic temple of eternal hope, where the unfortunate losers, though perhaps clutching a barstool or an illegitimate child, never surrendered. Both Diana and Frank seemed to triumph over heartache, and their visions seemed to complement each other, the yin and yang of pop: the pain expressed in “Love Child” seemed youthful, while Sinatra’s songs were about longsuffering. He'd had time to mull over what he’d gone through, and it came out in the smoky tones and whiskey irony. If he could survive losing Ava Gardner, couldn’t we survive our lesser, merely human disappointments?

Of course, I could not realize what stunning disappointments our family was to endure in the years to come: my mother’s second divorce, my own marriages and bitter separations. We act out the patterns of very ancient archetypes, figures of desire and betrayal, the mistakes and utter abandonment of goddesses and heroes, peasants and kings. Recently I discovered a wonderful section in Nancy Sinatra’s biography of her father when she remembers meeting Ava for the first time at nine or ten. One would expect some sort of Elektra-like jealousy, or at least hostility toward the woman who had supplanted her faithful mother. Instead, the child is totally floored by the beauty of the actress in her prime, and a sense of understanding of why her father had to be with this stunning Aphrodite. In the presence of such beauty all morality and kinship disappears since our first loyalty is always to the extremely beautiful and brilliant and charming. Blood and conscience fill in whatever blank spaces we cannot satisfy with those things we desire or appreciate, and then we rationalize our behavior. But as Frost reminds us, “So Eden sank to grief, / So dawn goes down to day. / Nothing gold can stay.” After Beauty storms out the door with all her stuff, and refuses to return any of our phone calls, we are thrown back on whatever talent we have been given to fill in the emptiness. And Sinatra’s voice had been so completely given to him by Nature and the hard hours of work that he could overwrite the zero with those almost tangible notes, that full and passionate tone one can almost taste and hold in one’s hand, a finely-worked ball of whiskey-flavored music.

I must admit that Nancy had greater generosity of spirit than I did at a similar age when my stepfather, Dick, was first seeping into our family. It was quite clear to me that I was no longer Mommy’s little man, but I was certainly going to defend my little kingdom as long as I could. When Dick came to dinner late one night after a long commute from New Jersey to the Pennsylvania town where my family lived, and sighed that he’d had a hard day, I responded with the most sarcastic “So?” a seven year old could possibly lob into a conversation. My mother, mortified, gave me the eye, and hissed my name in rebuke. I knew, instantly, that it was all over, and I dissolved into tears, which only mortified my mother all the more while she was entertaining this professional, college-educated man who was so interested in her. I could never have put this into words, but I knew my mother didn’t need me the way she needed a grown up man with a job and status I could not have for years, and I wept as the continent shifted under my feet.

And now it occurs to me that my mother was almost exactly the same age as Nancy Sinatra when I first became aware of her, though Mom never wore a miniskirt and I doubt she even liked Nancy’s songs. But I was hopelessly in love with Nancy for a year or two after Dick moved us over to New Jersey, closer to his job, a case worker for the Bureau of Child Services. In opposition to my erotic awakening at the image of a pop singer, I remember him showing me a series of photos of somebody’s daughter, a victim of abuse. In the first photo, the girl is sitting Indian-style on a gurney and smiling at the camera, a happy child. In the second, the arms of her pajamas are rolled up, and one begins to see the extensive cigarette burns everywhere a sleeve would cover. And then the pajama

|

top comes off, and then the bottoms, and you see it all. Clearly, there are fathers haunting the world who do not spoil their children, though they probably tell them that they do. Perhaps I was a part of Dick’s case study; perhaps he wanted to warn me of something. The little girl’s photos were a dark, sadistic version of eroticism, images that resonated with something inside me, as I still remember them, but that I wanted to forget. I remember watching a lot of television that year—it was 1966, the year of Batman—and I was fascinated by a life behind a cowl, the mod version of monkhood. Lots of stylized violence.

•

As they always do, the years melted away like cancelled TV series, and one’s erotic loyalties shifted. By 1974 I was mostly interested in the copies of Penthouse and Playboy Dick kept “hidden” under the bed. It never occurred to me to consider, during my own confused and repressed adolescence, in the midst of my inarticulate awe in the presence of Sunday’s music and the beautiful naked girls under the bed, that Frank was indeed the father of Nancy Sinatra, the girl on whom I’d had such a crush a few years before. She—or the image of her I drank in with my eight-year-old eyes and ears—was my sexual morning, the first woman I found absolutely compelling to look at. Her body and stiff sensuality made me deliberately ignore everything else around me in real life so I could look at her without interruption for the course of her all-too-short television appearances. When I was a child, the fact that she aroused me seemed so innocent and all consuming while we, as a family, watched her on some mid-sixties variety show appearance, that I was not ashamed, or even aware of my little physiological reaction.“Does he always do that?” my horrified grandfather asked as he left the room.

“Only when he sees her,” my little brother replied.

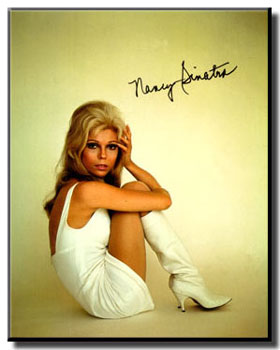

I was not especially aware I was doing anything; there was something about the way she offered herself up to one’s gaze that brought me out of myself. She wore her trademark form-fitting miniskirts and high white boots that invited you to look, but she carried herself like a good girl performing for her daddy. Despite the bare midriff and the leather fetish, there was something innocent about her, as if the general audience could only see her in relation to her father, and could not forget, as her very name reminded, that this sexy girl was indeed a great man’s little girl. Any adult looking at her image in the 1960’s would have thought: I am looking at her, looking too long and too closely—surely her father will know, surely he will see? Isn’t he an old friend of the family, haven’t we heard his voice in our homes and bars, our jobs and automobiles, haven’t we known him all our lives? And here we are lusting after his daughter, because she is teasing. And Daddy not only knows, Daddy encourages it.

In those days I only knew of her father in terms of The Established Artist, A Living Classic. His careworn yet beautiful face seemed to document an era my generation did not have to pass through, the Depression and World War II. But hadn’t he been a sex symbol as well? Hadn’t the bobbysoxers rioted and stormed after him long before Elvis and the Beatles? They had turned over cars to try to get to his skinny little body, to possess, if only for a miraculous moment, the flesh that produced that extraordinary voice, the instrument through which an amazing breath passed, transformed into pure sex. His throat was a kind of profane Eucharist, held in the monstrance of flesh, where the mysteries transpired. Frank was, of course, quite beautiful as a young man, but I suspect it was the voice that seduced the multitudes of girls, the smooth caress of floating desire. With Nancy, I think it was not so much the voice. It was the attitude she copped. Of course, it would be unfair to compare her to her father, as it would be to compare anyone to her father and his astonishing career; if anything, she was given less, but got more out of what little she was given. But what made Nancy sexy was her tight fitting Mod attitude (this was before the Summer of Love and the transformation of the Sixties from fashion to anti-fashion). She flirted brazenly with her father and his friends (Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Junior) especially in her television special, “Movin’ with Nancy,” but she was clearly of her generation as much as she was Daddy’s Girl.

In this 1967 NBC special, always officially described as “groundbreaking,” we find Nancy wandering around through northern California in one striking Mod fashion statement after another in a loosely-connected narrative that has something to do with urban alienation and the freedom available to young women in the Brave New World. It truly is a precursor to MTV and the whole concept of music videos that has so influenced our fragmented and frenetic postmodern vision, in that the emphasis is on the beautiful surface of Nancy’s face and legs, while the content is kept blissfully vague. She lip-syncs a variety of originals and standards as the scene shifts from one deserted location to another, the highpoint probably being “Friday’s Child,” which features an authentic San Francisco-Big Brother and the Holding Company guitar lead splashed across a sepia-toned oil field. The loneliness of all of these backdrops is only relieved by Nancy’s eventual discovery of her father in a crowded recording studio, as if we have finally made it to safety and warmth, and by the salvific appearances of Dino and Sammy. And when Sammy and Nancy engage in an extended spoof of Blow-Up, Antonioni’s attack on decent middle class notions of reality, and then dance together to “What’d I Say,” one is reassured that the counterculture is really no threat, and all in Hippie Good Fun. If the Rat Pack says psychedelic rock is ok, then maybe we can all get up and groove and wear those really tight miniskirts, as long as we keep them white as a schoolgirl.

But of course Nancy was hardly innocent. She had already been married and divorced by the time she became a media figure, and she seemed to have a very shrewd sense—almost a proto-Madonna—on how to use image to her advantage. It was her idea to record the song “These Boots Are Made for Walking,” her first hit after several false starts in the recording business (“Boots” became number one in 1966, and later a kind of feminist anthem). The story behind the recording is that her songwriter and producer, Lee Hazelwood, who fancied himself a kind of Hollywood Johnny Cash, had written the song for a man to sing. Nancy heard it and wanted to sing it herself, arguing that with a woman’s voice it would be fun, but with a man’s voice it would be mean and nasty. Hazelwood continued to resist until her father, listening from the next room, intervened and Hazelwood gave in. Of course she was right. With a woman’s voice, it was more than fun—it was sexy. Clearly this woman was far from innocent, considering the tough image she was creating. As Nancy reports in her biography of her father, Hazelwood told her to sing it

"Like a fourteen-year-old girl in love with a forty-year-old man . . . For chrissake, you were a married woman, Nasty, you’re not a virgin anymore. Let’s do one for the truck divers . . . Say something tough at the end of this one. Bite the words."

And so she gladly transformed herself into a Daddy’s Little Girl who can also give you the whipping of your life, a girl next door who you might just spot on the freeway riding a big Harley (she co-starred with Peter Fonda in a cult biker film, The Wild Angels). There’s something incredibly erotic about the little girl who can kick your ass just the way you like it, and walk away with a smirk shot over her blonde shoulder.

Of course, the bass line to “Boots” is deservedly famous as it starts low and then takes you down, down, down lower than you thought you could go, but what really makes the song is the deadpan delivery in her voice, like a Vegas Lou Reed bitch. This is “Walk on the Wild Side” meets the Rat Pack, with a kind of latent gender-bending in her androgynous delivery and promise of violence. At the beginning of every verse, the tambourine jangles like chains, and the drum rises like a whip coming down with an almost Motown-like insistence. This mistress knew exactly what we wanted, and was plainly willing to administer it. Could I, at such a young age, have seen something sexy in this? Surely not consciously, but I clearly understood that something was going on here, and I liked it a great deal. It was another version of the images of tortured little girls, except this time they were doing the torturing. Perhaps it was a kind of redemption, a buying back of what I’d seen done to females before.

But really, Nancy was not the only thing I found erotic in a similar pre-pubescent way. I have another memory of early arousal from the same time period, also from television, this time a circus-style variety show. A man and a woman, she in a shimmery blue skin-tight dress, acted out a mutual murder—she shot him, her shot her, she shot him again, etc. As she died, she clutched her chest, and the agony on her face was also the ecstasy of orgasm, though I did not know that at the time. Slowly, she slithered to the floor, and this utterly excited me, though I had no idea why or what this was all about. It wasn’t about the death—though the delirious sense of giving in to fate and necessity has often led our species to equate it with sex—it was her expression, as if we are hard-wired to be excited at excitement. Somehow I knew this had something to do with intense pleasure, and all the shooting was just a mask. Unlike Nancy Sinatra, however, the pleasure here was passive, as if she was taking something she did not entirely want, but could not prevent. With Nancy, her pleasure was subtler, taken without permission and enjoyed without apology. If it was at some man’s expense, he could deal with it, or not. She had better things to do than worry about him.

But she never entirely dared to remove the mask of innocence, as if, despite the fact we knew there was something going on, she could always claim she had no knowledge, to her best recollection, of anything sexual about her performance. And isn’t this the very thing that men find both irresistible and maddening about women, the accomplished prick tease in the glass tube, the untouchable, two-dimensional image? She craves not us, but our attention, and exists as our projection—yet not entirely so. Certainly, we see what we want to see, but there is also a sense in which we see only what the magician’s hand allows us. We feel desire, so we find an object with which to diddle ourselves to agony.

After many years in retirement and raising a family, Nancy returned to the job of representing desire with a nude portfolio published in Playboy in 1995, the year she released a comeback album, One More Time. She was fifty-four years old and, even factoring in the obligatory surgery and airbrushing, she looks incredible, though the voice sounds a bit rusty on the country originals and her version of “Knights in White Satin.” But what cojones to do the thing, to pose in the nude after your children are grown, a few pages down from a nineteen-year-old nymphet as perfect as she will ever be. Her face has, of course, changed with age and emendation. But there is something of Vague and Ageless Pleasure in these postures, especially one where she lies back and caresses the inside of one thigh, raised in a triangle over her bush, the face a blur of pleasure or its simulacrum. The editorial artist’s airbrush removes lines rather than accentuates them, blurring the body into the vertiginous polar whiteness of the bed sheets on which Nancy spreads herself. Here all the sharpness is removed and we are asked not to look very closely in order to create our pleasure, and give Nancy hers. Her pleasure, and a large part of ours, rests in the fact that she looks so good “for her age,” that she has triumphed over time in such a way that we can believe desire can never die, since we still desire her, thirty years after the original sin. But that pleasure, contained within her skin, can ultimately have nothing to do with us, as she admires what she looks like as herself, while we look on from a distance of space and, increasingly, time.

Just so, I have lived in the shadow of this woman’s body for much of my life, and her image was an important part in forming my sense of sexuality and desire. When I was a child, watching her on television, I was being taught something very important, the way this very evening, children are watching Britney Spears and being taught the lineaments of desire, how to look and how to feel. But there’s nothing here to fear, unless we’ve been reduced to fearing pretty girls or, in other cases, pretty boys. In our Brave New Century, we are trying to renegotiate the demands of our terrifying desire somewhere between Christina Aguilera and Madonna, looking for innocence on the verge of putting on her boots and walking all over us.

Thanks to the Nancy Sinatra Website, http://www.nancysinatra.com/, for photographs.